Last November, Toyota Motor announced to the world that it wants to be known as a mobility company, and not just a car company.

It did so with the launch of its Start Your Impossible campaign, partnering the International Olympic Committee and the International Paralympic Committee to tell the world that it makes more than just cars.

In September this year, the Start Your Impossible campaign was introduced to Singapore at a huge event underscored by Toyota agent Borneo Motors naming local Olympics gold medallist Joseph Schooling as its brand ambassador.

Toyota is not the only one heading in this new direction.

Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Volkswagen have gone into the car-sharing space.

Audi has rolled out its on-demand business, where consumers can rent an A3 hatchback or TT coupe for as short a term as four hours.

Renault has partnered Ikea to offer its vehicles for furniture delivery.

We have seen this coming for a while now. With the biggest automotive markets reaching maturity and saturation, car companies have had to look for new growth avenues.

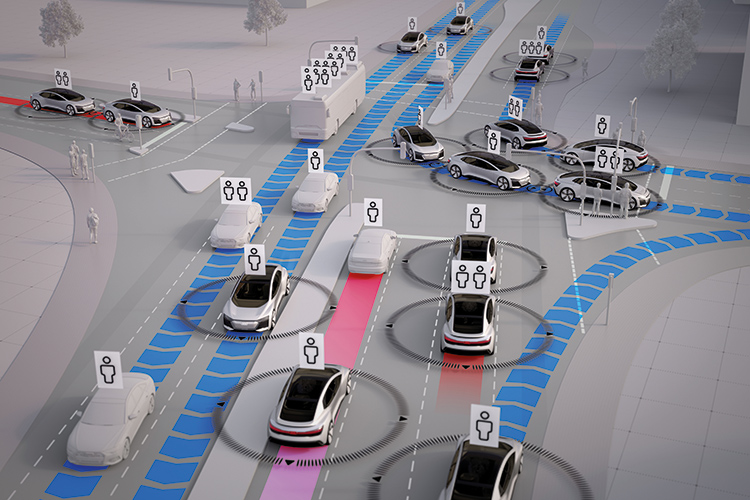

But this time, the quest to becoming a “mobility” provider hinges on the promise of autonomous technology. Yes, driverless cars.

Because when fully autonomous vehicles arrive (not before 2030), there will be a significant shift in consumer behaviour.

Consumers will not care which driverless car ferries them around, as long as one is available when they need one.

While there will still be many who will continue owning cars, others – perhaps the less well-off – should come to see cars as a service rather than an asset.

When that day comes, a sizeable portion of car sales will become fleet sales – in essence, (driverless) taxi fleet sales.

This will have profound implications for, among other things, advertising and marketing.

Will car companies need to spend the billions they now spend worldwide on advertising campaigns?

Will they need a marketing department staffed by MBA holders? Will they need to sponsor future Olympic gold medallists?

Probably not. And if they do, it will only be for cars targeted at folks who still want their own private transport – not to be shared by all and sundry.

In the case of Toyota, it will be reserved for its Lexus cars. And not all models, either. Just the high-end variants.

For the rest, there is no need for advertising and marketing, because of one simple reason – consumers will not care which driverless car ferries them around, as long as one is available when they need one.

When was the last time you saw a carmaker advertising its taxi model? So, there.

That does not mean carmakers need no longer compete. Each will still have to convince fleet buyers that their autonomous products are the best. So, the boardroom pitches, wining and dining, and plant visits will still carry on.

Fully autonomous cars will just be a mobility mode to be shared by all and sundry, not unlike buses or trains.

Media test-drives and lifestyle junkets, on the other hand, will dwindle. They will be confined to luxury and sports models.

Demand for car designers might dwindle as well. Because with autonomy, comes anonymity. End-users will not care how a car looks, as long as it arrives on time.

In the Singapore context, the COE system will also be pared down. If privately owned cars become a niche rather than mainstream, yearly COE quotas will become much smaller.

From a land transport perspective, that might be a positive outcome.

But from a government-revenue point of view, it would be a huge negative impact. The billions earned from COE bids each year could shrink to mere nine-digit figures, or smaller.

How will the Singapore Government make up for the shortfall? That is something worth pondering.

For car enthusiasts who have developed brand loyalty over the years, be prepared to have your world turned upside down, too.

Because the car as an expression of individuality, ambition and achievement will only be the preserve of the very well-heeled.

For the rest of us, the car will just be a mobility mode, not unlike a bus or a train.

Thankfully, not all of us will live to see that day.